If someone were being snarky, they could call it Atrocity Tourism.

I’ve visited two concentration camps, Auschwitz and Terezin, and multiple Holocaust museums. I've visited the Museum of Memory and Human Rights in Chile. Now I've also been to Hiroshima—its Peace Memorial Park and museum memorializing the devastation of the first atomic bomb.

My husband Sam and I stopped in Hiroshima on Friday, the last day of a three-week vacation in Japan. I’m glad it was the final day: Sam and I were able to view the memorial with some knowledge of broader Japanese culture. And a return to more sunny touristic activities after the memorial would have felt almost obscene.

I’ll describe our visit, and why Atrocity Tourism would be a misnomer.

Hiroshima today is a busy, modern city with skyscrapers, shopping arcades, and a baseball team (the Hiroshima Carp!) that happened to be playing a home game and so the streets were filled with fans in red Carp shirts. Several tidal rivers run through the city into a bay. We got off our tram near the bridge that was used as a target by the pilots who dropped the bomb. It’s a perfect target, an easily visible T intersection where one of the rivers splits into two at the tip of an island.

The first thing we saw was the Atomic Bomb Dome, the skeleton of a building that used to house business expositions and was a well-known city landmark. It was stunning in its stark eloquence. This was about 500 feet from the center of the explosion on April 6, 1945, and—having viewed my share of Hollywood apocalyptic movies—I easily imagined the blast and destruction starting here and radiating out in all directions.

Apparently there was a debate early on among Hiroshima residents about whether to leave the remains of the building standing or demolish them because they evoked so many painful memories. They made the right decision.

Many small monuments

The Atomic Bomb Dome stands on one shore of the river; we crossed a bridge onto the island, which is filled by the Peace Memorial Park. The park includes dozens of small statues and monuments scattered among walkways and patches of lawn. You can wander between them, which disperses the crowds and makes it easier to have a quiet and thoughtful experience. We didn’t try to visit them all but just meandered.

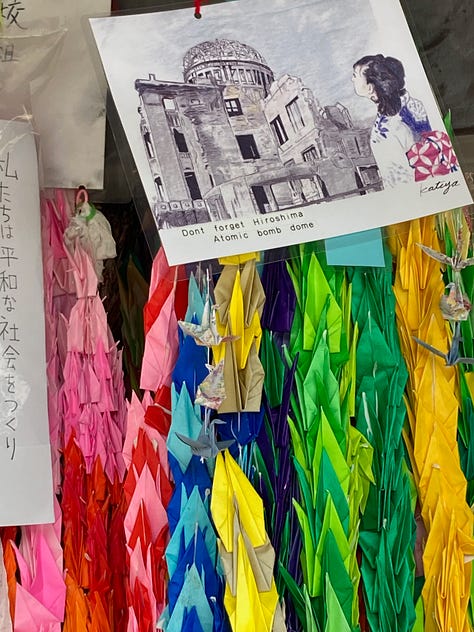

There was a Children’s Peace Monument consisting of thousands of paper cranes sent by people around the world who were inspired by Sadako Sasaki, who folded 1,000 origami cranes while dying of radiation-caused cancer at age 12. Sasaki became an Anne Frank-like symbol of Hiroshima’s human toll.

There was a monument for Korean bomb victims, most of whom had been sent to Hiroshima as forced labor and for decades didn’t receive the same recognition as Japanese victims. There was a monument for the student brigades killed by the bomb—junior high and high school youth who’d been sent to downtown Hiroshima that day to clear firebreaks between buildings.

The numerous small monuments reminded me of the Shinto shrines that dot every neighborhood of Japan. In Shintoism, you don’t need big, official cathedrals or temples in order to pray. There are shrines in homes, alleys, mountainsides, etc. to venerate the many supernatural spirits (kamii), some of whom have ties to particular natural places. In Hiroshima we saw some Japanese visitors approaching the bomb monuments like shrines—doing the bowing ritual that takes place at traditional shrines throughout the country.

We wandered across the island to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, where the entrance line snaked for about twenty minutes. After three weeks of visiting Shinto shrines, we saw echoes of shrines in the museum’s architecture. At shrines, an arched torii gate that marks the border between sacred and everyday space. Here, the arches of the building’s glass facade and the arch that the ticket queue passed through might also suggest that one is entering a sacred space.

The museum itself was as moving and profoundly disturbing as any Holocaust museum I’ve ever visited. The permanent exhibit opened in a room surrounded by a large panoramic photo of Hiroshima right after the bomb, and a digital/video diorama showing the bomb falling and then the explosion spreading. This was a gee-whiz kind of room for those of us who read science fiction and try to imagine apocalyptic scenarios – horrible, but also fascinating.

Then things got less fascinating and more personal.

Depicting the human toll

We moved through multiple rooms about the human toll of the bomb. There were artifacts such as shirts worn by victims that still show dark stains from the radioactive “black rain” that fell right afterwards. Even today, 78 years later, those stains register as faintly radioactive.

There was a belt worn by a young boy whose clothes were burned off and who stumbled home naked clutching his belt, a recent gift from his parents. He died within a day. There were photos of victims and quotes from their family members. There were drawings done by survivors decades later, when Japanese news media put out a call for survivors to share their memories. There were gruesome photos of corpses and burn victims.

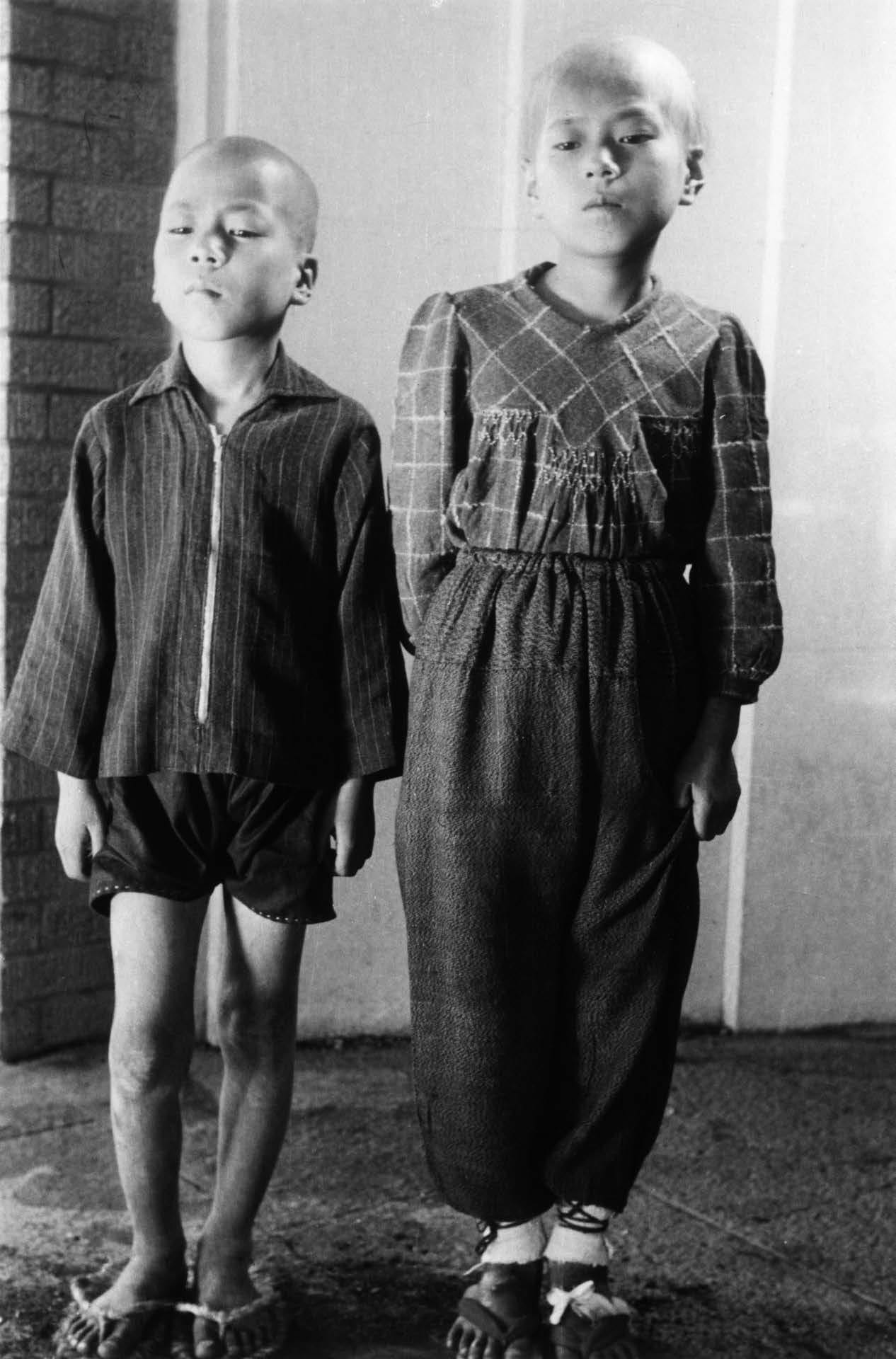

There were several images of a young brother and sister who lost all their hair within days of the bombing and then suffered longer-term radiation poisoning; the boy Toru died four years later at age 11 and the girl Aiko died of cancer twenty years later of cancer at age 29.

You get the idea. It was individual and personal and intense. It made clear that the damage was indiscriminate and long-term—not just the estimated 140,000* deaths of the first year but a physical and psychological toll that went on for decades.

Part of the horror was the bomb’s unprecedented nature. Unlike other conventional bombing raids, the U.S. dropped no leaflets warning residents of the pending attack. And when it happened, residents had no clue about this new kind of threat. Parched with thirst from the heat, they didn’t know that drinking the black rain meant ingesting radiation. Nor did they understand why their loved ones had tongues turning black, skin turning purple, guts vomiting out.

When survivors are gone

We watched a video focused on survivors—hibakusha is the term for them, which literally translates as "bomb-affected person"—and how that generation of 80- and 90-year-olds is now passing away. The parallels with Holocaust survivors were unstated but felt so clear to me. Both atrocities raise the same question: How can we continue to convey the horror and the message of “never again” when the generation of eyewitnesses is gone?

I was also struck, with sadness, by a big difference. The Hiroshima museum needs only to convey the human toll of atomic warfare and why it must never be repeated. No one questions whether the atom bomb was really dropped and whether 140,000 people died from the blast.

Holocaust memorials, on the other hand—and all of us who care about the Holocaust—face an additional, infuriating task. We need to refute the Nazi apologists and anti-Semites who continue to claim the Holocaust never happened. That’s not a challenge faced by the Hiroshima museum: as far as I know, there are no “atomic bomb deniers.”

Politics that led to the bomb?

We were overwhelmed and moved by the exhibits on the human toll and danger of nuclear weapons. But I had mixed feelings about the overall messaging of the museum, which was notably devoid of political context. You might summarize it as:

An atom bomb fell on a city. The human toll was devastating. Nuclear weapons must never be used again.

Unlike some memorials we visited in Berlin that addressed the rise of Nazism, there was no critique of the political roots of World War II. The museum did not discuss Japanese militarism and expansionism, which ultimately caused the war. The message was a simple one that would be hard for anyone to argue with:

An atom bomb fell on a city. The human toll was devastating. Nuclear weapons must never be used again.

I don’t know. Part of me wished the museum would challenge Japanese to examine their own responsibility for a war that ended with such an atrocity, and would also challenge Americans to question whether the bomb was truly militarily necessary. Another part of me felt like the basic, simple message of “no more atomic bombs” is important enough to stand alone.

Certainly it’s a message I hope the G7 leaders hear when they meet in Hiroshima in a few weeks.

Certainly it’s a message that today—when more countries than ever have nuclear weapons, Russia is waging war on Ukraine, and U.S.-China tension is at a renewed high—leaders everywhere need to hear.

“Atrocity tourism” is a snarky label, but there is an important place for this kind of visit. If we’re privileged enough to fly across oceans to experience the food and art of other countries, we also have a moral obligation to learn about their darker times, especially if we as Americans were involved or responsible. I loved our three weeks of cultural tourism in Japan—seeing historic shrines and temples, eating bento boxes in train stations, bicycling along beautiful coastlines—but the museum engaged me on a deeper and more personal level.

Viewing shrines and temples, I'm a spectator from another culture. Viewing Hiroshima, I am a participant—both as a citizen of the country that dropped the bomb, and as someone living in a world where nuclear weapons could too easily be used again.

An atom bomb fell on a city.

The human toll was devastating.

Nuclear weapons must never be used again.

*The actual number of people killed at Hiroshima can only be estimated. The museum puts the figure at 140,000 who died within the first year, with thousands more dying later from radiation-related conditions. Other estimates range between 70,000 and 140,000.

Ilana,

I have enjoyed seeing photos of your trip and this piece was especially well written. Having just returned from a Rhine cruise, I was struck by how all our tour guides made a point of how Germany and the German people have gone to great lengths to examine the roots of their own anti-semitism. Posting any anti-semitic filth in Germany now is a punishable crime. I'm not sure this is the right approach as free speech - no matter the content - should always be defended. (an issue we are grappling with here in the US at this time also). I did not get the same impression when we toured areas on the French side of the Rhine - and if you follow current events, anti-semitism is clearly still alive and well in France. I do agree with you though that Japan would also do well to examine the rise of their own extreme militancy, as we would do well to question whether we were wise in dropping the bomb on Hiroshima. Anyway - thank you for this evocative essay.

Atrocity tourism is a reasonable label; within the umbrella designation of "dark tourism," a subset including mainly war-and-politics related historical tourism. (For instance, Pompeii is dark tourism, but it's not atrocity tourism, since it was the product of a natural event. Still, the phenomenon of Pompeii includes plenty of heritage & culture components.) Dark tourism is actually a large field within cultural/heritage interpretation. Speaking as a member of the National Association for Interpretation. But however we label it, it is generally very moving; generates understanding and empathy for the victims of atrocities. Never forget; never again.